Building and Flying a Pitts S-1T Airplane

With a Pitts S-2E and a 1947 Aeronca Chief on the Side

Thousands of amateurs have built and flown their own airplanes since the beginning of manned flight, in a time before flying machines were even called airplanes. Plans for a bi-wing glider were found in a 1913 copy of The Boy Mechanic, fully described in a page and a half of text and one drawing. In the early 1930s a series of magazine articles covered the construction of a Pietenpol Air Camper, a high-wing monoplane built of wood and powered by a Model A engine. In the 1960s or early ’70s Popular Mechanics magazine published a set of plans for the Volksplane, a wonderfully simplistic and boxy airplane powered by an air-cooled Volkswagen engine.

Plans-built aircraft are still plentiful, but kit-built aircraft, where many of the sub-assemblies are supplied factory-made have increased in popularity. As long as the builder performs more than half of the overall construction effort the aircraft can still be considered amateur-built, operating with a special airworthiness certificate in the experimental category. The freedom to innovate designs destined for this experimental category – without the constraints of type certification – has resulted in a large number of amateur-built aircraft that exceed the performance, efficiency, and in many cases the beauty of production aircraft.

This is a story about how one of these amateur-built airplanes came to be.

In the process of organizing all of our film and digital photos recently I started picking through the hundreds of photos that we took during our aviation years while attending EAA conventions and working on our own projects. Most of the convention photos were of various display aircraft that may have been important at the moment and yet are of no special interest now. But occasionally I would run across a scene that held more significance – an emotional flashback to people, places, and times that are gone.

My original intent with this blog post was to write a short article to explain some of the more interesting airplane construction pictures that had amassed over the years. But as I look through the photos and remember, I am writing something else, for myself. Writing about a period in your life nearly 30 years after the fact is not something that I have done or intend to do again, but the events that consumed the better part of a decade must have left an impression. It is difficult now to feel the motivations that drove me at that time, but I do still understand them and the path that led me there. These were good times, and it wasn’t all about airplanes.

The Circus Comes to Town

If memory serves correctly, it was in 1970 when an event came to the Wisconsin town where I was a teenager, and it left an indelible impression. Normally the only events of any significance that came to that area involved snowmobiling and the heavy consumption of alcohol, not necessarily in that order.

The event was Expo 70, an airshow and aircraft exhibition that came to our local airport on what turned out to be an unseasonable day in the middle of summer.

Other than the bitter cold and wind of that day, one thing stands out, and I remember it well. It was the featured aerobatic flight demonstration of a little red Pitts Special biplane. If I recall correctly it was flown by one of the pilots of what was to become known as the Red Devils flying team and later the Christen Eagles flying team.

Thinking back today I really don’t recall anything about the performance beyond the takeoff. But what I do distinctly remember was that as soon as the plane roared off the deck the pilot executed a very low-altitude 4-point roll, holding each point long enough to stretch the maneuver over the length of the spectator area.

I had never seen anything as spectacular as that, ever. At least not since the July events of the previous summer. These were exciting times.

That mental video (before we had videos) played in my head repeatedly for years. I would relive it before falling asleep, and while daydreaming through high school classes. I imagined what it would feel like to be inside the cockpit looking at the ground and the sky from the different orientations. But in that time and place there was no path to follow that would allow me to get close to something like that, any more than I could have become an astronaut and walked on the moon as I had imagined the previous year.

Shortly after this airshow I became fixated on the construction of a rigid-wing hang glider, the plans for which I had found in a magazine of the time, probably Popular Mechanics. It was a full three-axis glider that used a large aluminum tube for a tail boom and had built-up wings with conventional ribs made of spruce and mahogany aircraft plywood. I ordered some materials from B&F Aircraft Supply and started building what I could, without any realistic strategy for completion.

Some pretty commendable progress was made on a set of wings and tail surfaces before reality set in. I was 17 years old at the time and circumstances were such that there was no access to the equipment that I would need to finish it nor any of the minimal training that would be required to safely fly it. It turned out to be an absurd waste of money, as those around me had predicted. Under threat of having the wings cut up for me while at school (in order to vacate the garage in which they were stored), I chose to do it myself. All was not lost; to this day I still have some leftover sheets of 1/32″ birch aircraft plywood that come in handy from time to time.

Although I came from an environment where attending college was not in the plan, a turn of events allowed me to escape and for the next few years pursue an electrical engineering degree at UW-Madison. During my junior and senior years I started to work through a flight training program at the Dane county airport located at the opposite end of Madison from the campus. Lessons would be scheduled as funds permitted and eventually I received a private pilot certificate.

After graduation I went to work in the aerospace industry (or MIC as we know it now), and as fate would have it I came into contact with two fellow employees that were either building or had built their own airplanes, both of which happened to be Pitts biplanes.

Bill was a senior engineer in my department who quickly became both an engineering and aviation mentor, and would remain so for the years that I was there. He was a cool and accomplished pilot, mechanic, and builder, and on a part-time basis performed at airshows and in competition. He provided guidance to get me started building an airplane and advised me at every step along the way. He also rode front seat and taught me how to fly and land a Pitts S-2E, and when the time came he was there to test fly my newly-built airplane on its maiden voyage.

The second influential co-worker was Jim, a supervisor in another department that was building a Pitts S-2E from a kit. He invited me into his shop and his life, becoming a great friend to both my wife and me and trusting us to help with his project. He allowed me the use of his shop and welding equipment before I could afford to have my own space, and he helped us all along the way. To this day I will still remember him as the most fun, selfless, and generous person I have ever encountered throughout life. After having lost contact with him in the early ’90s I was sad to learn that he recently passed away.

I have lost touch with many over the years but I will never forget the encouragement and friendship of all of these people, including my flight instructor, and I fear that I never was able to return what they gave to me.

Itching to Get Started

By the time I began in engineering, most of my co-workers were building families and buying their first houses. Once I got on my feet, actually within the first year, I started ordering aircraft materials with whatever funds remained after paying the rent and school loans.

Since I was helping Jim with some of the simpler tasks involved with building his Pitts S2E, and all of his components were right at hand and readily available to look at, it seemed logical to start building a similar but slightly customized design.

The S-2E (E for experimental) was a two-seat redesign of the original single-seat airplane designed by and named after Curtis Pitts. It had a symmetric wing airfoil and was designed to use a 180 hp Lycoming engine and a fixed pitch prop. Although it had a full canopy option available, Jim was building his as an open cockpit model with dual windshields. I planned to build a similar fuselage that would accept a full canopy design similar to that used on the Christen Eagle.

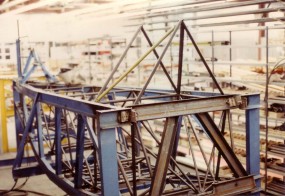

It took more than a year to build a complete welded fuselage and tail feathers, and more time yet to build the engine mount and control system. Most of the fuselage was completed in Jim’s garage, but it soon became time to look for a nearby hangar for some extra working space.

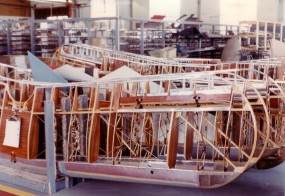

During breaks in working on the fuselage I began building a set of wings in my apartment. The apartment had one long wall that ran from the dining area into the living area, with a straight shot out the patio door (fortunately it was a ground level apartment).

Along that wall two table saws, a drill press, and sawhorses were set up. A new air compressor adorned the dining area, but it was only being stored on its way to someplace else (thankfully there was no 220v outlet in the dining room). Any measly furniture that had been inherited from home or college was relegated to a corner, with chairs upended like tavern stools at closing time. I essentially lived in the bedroom, which was really not much different from the living conditions I had just left behind while attending college.

The upper wing spars were well under way when it looked like it might be a good idea to put some carpet protection down, and everything was moved out to put some protective pads in place. After seeing the carpet again in these photos, this step could have been skipped.

Building wing ribs was highly repetitive work but it also was a great way to spend Christmas vacation in the apartment. Each rib was made of spruce sticks, an average of 18 plywood gussets, and roughly 150 1/4″ long nails. And there were something like 44 ribs just for the wings on the S-2, not counting the small ribs needed for the four ailerons.

The wings were also an ideal apartment project. Even assembling the twenty-foot upper wing was not a major problem, although the occasional end flipping had to be accomplished by scooting out the patio door, rotating, and slipping back in, usually in the dark of night. The two lower wings were no hassle at all.

The woodwork for the wings was completed in the apartment, and the fuselage was progressing in my friend’s garage. It was getting to be time for things to start to come together, and I needed space.

Fortunately around this time my “business partner” Becky (later wife) had bought a 1947 Aeronca Chief in need of restoration, and with both projects it became a little easier to justify renting a hangar. Everything moved to a hangar at an airport that was very close to our apartments.

Nosy Neighbors

At one point earlier when I was in the midst of wing building I learned that one of the building caretakers had been inside my apartment and had seen my project. They were not generally supposed to enter without notification, but they did anyway.

The caretaker was more curious about the project than anything. Of course over time he couldn’t contain himself and others found out, but they never had real cause to give me any grief. There were no hazardous materials, any noise was limited to very short table saw runs, and any other machinery was no louder than a vacuum cleaner. Messes were confined to dust and chips on carpet pads, and I kept that pretty clean.

S-2E Wing as Seen on Surprise Inspection by Apartment Buyers –

Next Time Call Ahead and I’ll Feather Dust For You

One time this same caretaker came to my door and was fairly agitated. The apartment complex was being sold and the prospective buyers had toured some sample apartments, and apparently my unit was on the tour. The buyers had apparently freaked out a bit when they first saw the nearly-finished upper wing and the machinery, but in the end they laughed it off and decided there was no harm being done.

Another time in passing he was excited to tell me of another resident of the same apartment complex that also appeared to be building an airplane (he had obviously been in that apartment too). I just laughed – that was Becky’s apartment and she had some Aeronca parts scattered about .

Later when I was working on a different set of wings I bought an ultrasonic motion detector alarm and placed it under my couch in silent mode so that any trips would be visible only to me. The first time it indicated a breach I called the office and asked who had been in apartment, and for what reason. They first denied it, and when that didn’t work they protested the idea of an alarm, but they had to live with it. It did put an end to the unauthorized visits.

A Course Change…

Somewhere around this time Jim finished his kit-built S-2, and a whole new world opened up to us. Any aerobatic training that we had attempted prior to this had been limited to a Cessna Aerobat, and maybe a Citabria in Jim’s case. Now we could do whatever we wanted whenever we wanted.

Jim loved to give rides, and he seemed to have no shortage of passengers willing to go. Even the occasional vomit-covered windshield was no deterrent to him – it was all good fun and all part of the show.

I wasn’t so sure. I had quickly used up my list of potential aerobatic passengers; some had been forever lost just doing spins, which don’t even really count. I started thinking that this might be a solo sport, and if so I didn’t want the extra weight and performance hit of having the second empty seat.

My custom S-2E project now had been completed to the point that it was due for a pre-cover inspection. After some mental anguish and the thought of having lost a couple of years of labor it looked like perhaps the best strategy at this point would be to sell the inspected two-seat airframe. I would use the proceeds to buy a factory fuselage and other major weldments for what would now be the current single-seat model Pitts S-1T.

I did sell my project after placing an ad in Trade-a-Plane. I’m not sure why the buyer wanted it, because he knew very little about the Pitts or any other airplane it seemed. I always wondered whether he finished it.

Off to Wyoming

The S-1T model was the latest high-performance single-seat design from the factory. It had fully symmetrical wing and aileron airfoils. But instead of using a 180 hp carbureted engine with a fixed pitch prop as did some of the earlier S-1 models, the T model called for a hard-to-find version (IO-360-A1E) of a 200 hp Lycoming fuel-injected engine coupled with a variable-pitch prop. The fuselage had been redesigned primarily in the firewall area, with a different cabane structure as well, and I was really intrigued with the idea of having that constant-speed prop on a Pitts.

Although the complete build plans were not yet available for the S-1T model, they were at the printers according to the manager of Pitts Aerobatics. The T model was to be offered as a kit, or as an alternative full fabrication plans would be available for the scratch-builder. I was planning to buy some factory parts, but I was approaching the project as a scratch-built custom model and I would need that complete set of plans. I had already received enough preliminary information to proceed with wing-building, and with the understanding that full plans were forthcoming I chose to purchase only those assemblies that were most economical to buy rather than build.

The Pitts factory was located in Afton, Wyoming not far from the Tetons. My business partner and I made a vacation out of the trip and visited the sites on the way out: looking for mother ships at Devil’s Tower, visiting the set of North by Northwest, and totally ignoring Wall Drug.

We were given a nice tour of the Pitts factory by Herb Andersen himself – to an amateur builder the tour alone was worth the trip. Another nice gentleman in the shipping area spent a couple hours helping me load boxes and mount the fuselage to my pre-made roof mount. As you might expect in a location like this the work environment looked informal and relaxed, but the factory had all the characteristics of a tightly-run production facility. Lighting was excellent, the floors were spotless, and everywhere you looked there were long aisles of shelves or racks loaded with stacks of everything from small steel brackets to finished wings. And they had a few freshly built planes all lined up ready to go.

The trip back would have to be a straight shot. The mini-pickup would be loaded with parts and a fuselage tied to the roof, and I really didn’t want to leave it in a hotel parking lot overnight.

Once we made it back home, everything was once again hauled into the apartment. Since a new set of wings needed to be built, having the fuselage right there to confirm clearances and alignments would be useful.

More Wings

The S-1 Pitts has slightly shorter wings than the S-2, and the total rib count this time was less. Otherwise the build procedure was the same, and Christmas vacation was again dedicated to rib-building, this time a year later.

Now when the wings needed to be checked against the fuselage fittings, there was no need to haul anything – the fuselage was set up, ready and waiting. There was enough room in the apartment to have the fuselage up on the landing gear, with both wings attached, and with the engine cowling in place. It spanned two rooms and a hall to do it, but it fit.

I think I may have even may have watched TV from the cockpit at some point.

When the S-1T wing set was finished and all that could be accomplished at home was done, everything was moved to the hangar (now a heated one) so that the structures could be covered, sealed, and painted.

It was around this time in late ’83 or early ’84 that I contacted the factory again to check on the status of the complete plan set, only to find that Pitts Aerobatics had been sold to Christen Industries. With the change the S-1T would now be offered only as a kit or a fully factory-built aircraft; a full plan set for scratch-building would no longer be offered.

This would have left me in a bind, but eventually I received assurances from Frank Christensen himself that the information would be made available as needed, and in most cases it was.

The Aeronca Chief restoration was on track to be completed well before the Pitts, and there were times when I came in to assist Becky with her project. I in turn received help from her on my Pitts, particularly the covering, when the time came.

At one point all effort went into finishing the Aeronca, and in 1985 it was completed and flown for the first time since it was purchased and torn down. That summer Becky and I flew it to the EAA convention in Oshkosh, and her restoration won Reserve Grand Champion in the Classic Aircraft category. We had absolutely no idea that this happened while we were at the show or afterward; a couple of weeks later a box containing a Lindbergh trophy just showed up on the doorstep. The story of her restoration project was covered in the EAA’s Vintage Airplane magazine and can be found in this issue starting on page 14 and including the back cover photo.

Engine and Accessory Rebuild

With the Aeronca finished, the focus returned to completing the Pitts airframe and engine.

The engine for the S-1T presented a unique challenge from the beginning. The I0-360-A1E engine specified for this model had a front-mounted propeller governor and was very difficult to find. The more common rear-mount governor on the A1D version of the engine would not work with the sloped firewall of the S-1T fuselage. Purchasing a new -A1E engine was out of the question.

The governor is actually an oil pump that provides variable oil pressure to the prop depending on the engine rpm and the setting of a cockpit control. This oil pressure operates a piston in the variable-pitch propeller hub which in turn varies the blade pitch. This forms a feedback loop where any potential increase in engine rpm is met with increased blade pitch, loading the engine to maintain a constant rotational speed.

Fortunately Ken Maxwell of Maxwell Aircraft Service in Crystal, MN came up with a solution. He modified a governor to mount on the vacuum pump pad of the engine’s accessory case, which was in a higher position that would provide adequate firewall clearance. The governor was calibrated to operate with the different gear ratio, and all was well. When the time came, the governor worked flawlessly.

This solution enabled the use of a more widely available A1D engine, and a first-time runout engine was purchased from a local engine shop. A factory-new solid-flange crankshaft was also purchased from Lycoming to replace the original crank. Standard crankshafts have holes bored between the threaded holes to remove a little weight. Unfortunately a few aerobatic aircraft had been losing propellers in flight due the standard prop flange cracking around these lightening holes. Even if a prop departed the aircraft cleanly, the pilot would still have to contend with a rearward CG shift and an immediate forced landing. As recently as a couple years ago I saw a Pitts engine that had lost the flange and prop. It was impressive, and the damage was not limited to the crankshaft.

Over the period of several months I overhauled the runout engine to new specifications, which was a very immersive experience in itself. The concept of rebuilding an aircraft engine does seem terrifying to some (including myself initially), but I later found this fear to be unwarranted in the context of the overall project.

Anywhere that you turn in the an airplane-building or restoration project you can find a potentially life-critical element, whether it is a single critical bolt controlling the elevator linkage or a connecting rod stretch-bolt inside the engine. Rebuilding an engine is really no different from building an airframe. Experience is certainly helpful but not required. Without experience to draw upon, you read, research, or stop and ask. Nothing is taken for granted, there is no guessing, and nothing is left unchecked. Engine manuals give specific requirements for the particular make and model, and general powerplant training manuals provide more generic overhaul procedures to fill in the gaps. And of course it always helps to have an engine expert or two to consult for confirmation or clarification of a point if needed.

A pair of impulse magnetos also needed to be rebuilt for the ignition system. These required the same care as any other part of the engine, but this is not rocket science. These engines are old technology and not complex – they just need to be reliable.

Covering and Painting

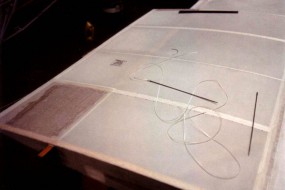

The airframe had been partially assembled at various times in the build process in order to check fits and clearances, but prior to covering it needed FAA inspection and sign-off. Everything was slipped together and wheeled out for one last look:

Once the inspection was completed, the airframe was ready to be covered using the Stits Polyfiber process. Becky did virtually all of the wing covering, taping. and stitching to the same level of perfection that helped her Aeronca win its major award.

The paint finish on a fabric-covered aircraft consists of many layers of different coatings. In this process the first coat was a clear sealer and adhesion base, followed by several silver coats (aluminum powder in a binder for UV protection), and lastly multiple color coats and trim, all sanded in between layers. A pressure pot was a necessity for spraying on the full wet paint coats, and when set up to paint the large wings we could blow through a gallon of silver or color in less than three minutes.

The Stits Polytone color finish is a flexible solvent-based coating that usually dries with a matte finish. Both the Aeronca and the Pitts used the same paint system, and both were machine polished to make the finish glossy. The finish was often confused with a two-part DuPont Imron finish that was used on the Christen Eagle aircraft, but it was not as glossy as that.

I was never able to achieve a high quality finish on metal parts using the Stits two-part Aerothane polyurethane that had been recommend for its extra durability. The finish was never free of what appeared to be airborne dirt, and the pigment seemed thin. I assumed that the problem was with my application or painting environment, but after giving up and buying Ditzler Deltron polyurethane, I found painting to be much easier. Later I compared the paints and found that the Aerothane was loaded with small flecks of pigment, small enough to pass through my paint filters but large enough to look like entrapped dirt. Several hundred dollars worth of this paint finally ended up at my local hazardous waste drop-off just a couple of years ago.

The interior sides of all the sheet metal panels in the cockpit area and the turtledeck were painted with a two-part black epoxy using a spatter-painting technique. A conventional base coat is applied, partially dried, and then followed by a uniform low-pressure sputtering of paint droplets over the entire surface to form a texture. This finish hides blemishes, looks great, and is tough as nails. I love this paint technique and still use it on many projects to this day.

Final Assembly

There were no major issues on final assembly. When all the components were painted, finished, and polished the real fun began and things practically fell together.

Hanging the engine on dynafocal mounts was a wrestling contest, but that was expected. Installation of control cables and fuel, oil, and brake lines in fuselage section around the fuel tank and the engine compartment forward of the firewall took the longest time. Hose routing was a bit of a challenge with no installation drawings, and the custom governor had to be dealt with. A Christen inverted oil system was installed and the oil and fuel system hoses were made on the spot to fit the installation.

Wing rigging and tensioning of the flying & landing wires took some time – this was not a good place to make a mistake. Everything else was mounted, rigged, wired, plumbed, and critical hardware was locked with safety wire.

The plane would have no battery and no electrical system. If and when a radio was needed it would have to be a portable with its own battery. The CG envelope for the S-1T was such that with my weight (I’m 6′ 2″) having a starter battery on board would push the CG too far aft for my comfort level. A starter still could have been used with an external battery and cable setup to avoid the need for the on-board battery – a standard (heavy) starter had come with the engine – but to keep the weight down I chose not to use any at all. This was probably a mistake in the long run, and ultimately out of necessity a starter and power receptacle were installed a few years ago.

The aircraft received a final FAA inspection and it was cleared for a generous test flight area that was large enough to include an airport with a grass landing strip west of the city.

Test Flights

Test Flight 1 – Bill

Bill and I had an understanding long before this day that he would be handling the first test flight. He had been giving me dual training in the S-2E to practice landings, and he was intimately familiar with the construction my aircraft. We usually had daily briefings at work, and his hangars were within walking distance of mine – he was confident in the plane, and I wouldn’t have let him near it if I wasn’t absolutely confident myself.

I was not too concerned about the mechanics of flying an unfamiliar plane (there was no way around that anyway), but any flight issues related to rigging or engine could have been much more of a problem for me than Bill, who had already had a few incidents under his belt, including an emergency highway landing a few years earlier.

After an extensive preflight I got him started and he was off. The plan was for him to orbit the airport above pattern altitude for a period, and if there were no issues, go further. He circled a few times, less than expected, and headed off. After about a half hour he returned and taxied in.

The first thing I noticed was the G-meter high-low markers pegged at a little over +6 and -4.5. That was a good sign. He had felt comfortable enough to perform some maneuvers.

In his heightened state (not excited – Bill was a cool guy and did not excite) after the flight I remember him rattling off some observations like any test pilot giving a debriefing. I don’t remember anything significant except he did recommend that a small trim tab be added to the rudder to trim out some yaw, which is fairly common. There may have been some other things, but I don’t remember.

Test Flight 2 – Me

Bill had advised (strongly) that my first landings be attempted on grass. The Pitts S-1 is short and can be unstable on roll out after landing – the grass would be more forgiving. I wasn’t very familiar with the FAA approved destination airport and terrain around it, but this was the plan and I intended to do some touch and goes until I felt comfortable enough to return to my home airport with its asphalt runway.

I picked a clear day, took off work for the afternoon, and headed to the airport. It was actually getting later in the day when I was finally ready to go, but it seemed like I would have plenty of time. I started the engine and taxied out to the runway, checked the mags, and cycled the prop.

I lined up on the runway and hit the throttle. The first thing I noticed was the amazing acceleration compared to the other Pitts. It was also much lighter on the controls and more instantly responsive to roll than the S-2. I was off and gone in no time at all, and everything was fine until the air started getting rough. I had expected some mild CAT, but I was seriously bouncing around and even banged the canopy with my head a couple times (or it banged me). I was moving around in the cockpit a little more than I would have expected and I was unconsciously taking the control stick with me. I do remember that there was a distinct rush of impending panic at about this time.

All of this happened before I had even throttled back from takeoff and I was probably at 3000 feet by now, watchful for planes but as yet unaware of where I really was on my route. I grabbed the stick halfway down so my gyrations wouldn’t induce more movement and throttled back. I was calming down a bit by now, and I set the prop and manifold pressure for cruise, but it was still too twitchy and rough so I throttled back more. Immediately everything felt better – I felt like I was back in the S-2.

I had not anticipated that the slightly higher airspeed and lighter controls compared to the S-2 would make the airplane feel as dramatically different as it did, otherwise I would have throttled back sooner. The other thing I had not expected was the noise level. I was wearing ear plugs with a David Clark headset, but I could tell the noise was higher than in the open-cockpit S-2. I think the acrylic canopy acts as a reflector, and your head is at the focal point.

By the time I recognized the terrain around me I had overshot the destination airport, but I was high so I just circled back and descended into a pattern. The first landing was as close to perfect as I could have hoped, but it honestly felt like a controlled crash. There is no forward visibility in the Pitts when on final – you have to maneuver to seen the runway. And visibility on flare is nonexistent – you have to hope that the Cessna holding short sees you and isn’t relying entirely on his radio.

I wanted to stop, celebrate, and admire the intact airplane, but instead I taxied back and did another five full-stop landings (not all as pretty as the first) before I would allow myself that victory. I pulled off the runway found a spot to shut down.

To make this story short, I dawdled for a while talking to a resident pilot who had witnessed my landings and soon decided I had better head back to the home airport. The thing about the fuel-injected engine is that you need to start it immediately after shutdown, or wait for it to cool quite a bit before restarting. The engine floods on its own very quickly after shutdown as the fuel injection manifold heats and shoots fuel into the cylinders. Hot starts take time when hand propping, and it was getting darker.

The pilot that I had been talking with offered to hand-prop me, but after a quite a few failed tries I called it off, not wanting to subject him to the cardio workout that it would take to get my warm engine going. He was kind enough to offer to hangar the plane overnight and drive me to meet my wife, who was still waiting for the little red plane to return from the sky. The next day I got a ride to retrieve the plane, took off and spent a fair amount of time in the air getting familiar with the flight characteristics. After playing around for a while I returned and landed on the asphalt runway of my own airport without incident.

EAA Convention

Of course one of the big motivators in building your own airplane is to be able to show it off at The Show of Shows, the Experimental Aircraft Association convention in Oshkosh, WI. For many years prior we had attended the show and admired the unbelievable craftsmanship of the amateur-built aircraft and the restorations of antique and classic production planes. It was a place to be totally immersed in aviation for a week, and if you had an airplane to show, it would have to make the pilgrimage.

Flying into the event during the heaviest influx of traffic is an experience in itself, with special approach procedures in place prior to the start of the convention. During the years that we attended by air the traffic would converge near Ripon, WI at two different altitudes based on aircraft speed. Controllers on the ground near this convergence point would advise pilots where to fall in line, generally asking for a wing-wag response rather than a radio reply – controllers were often transmitting continuously. Planes would form a line in front of and behind you, and in the case of the Pitts I had to throw in some lazy S-turns to prevent tailgating. There was very little need and often little tolerance for talking back to the controllers – you listened, followed instructions, and those that got out of place were often told to break off and circle back to start over at Ripon.

Once the planes approached the airfield, they would be alternately diverted left or right to different runways, and during the busiest times planes would be asked to touch down either at the end of the runway or midfield. At times they were landing some aircraft side-by-side, one cleared for the runway and the other for the taxiway parallel to the runway.

It was a very busy event, and part of the entertainment for the many years that we attended was to be settled in at the camping area during the heaviest traffic with an aircraft radio, watching the planes lined up as far as you could see and listening to the controllers.

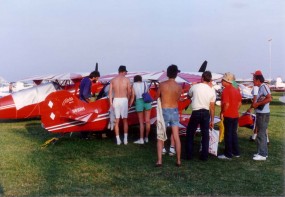

N68RH made it to the EAA Oshkosh convention only twice. On the first trip Jim flew his S-2 down at the same time, and we ended up parked next to each other at what is one of the most prime locations at the show – the end of a row near the spectator fence at show center. We had ground support with us so there had been no need to haul anything other than ourselves in the planes. It truly was a memorable time for all of us that were involved.

It was at this convention that the Pitts managed to pick up an Outstanding Workmanship award in the Custom-Built category in 1987 (they award several of these). I still think that it probably should have gone to someone else. My Pitts was nice for a Pitts, but at that show you could probably find a couple dozen planes in the Custom category that were more custom and more deserving. Nevertheless, that trophy and this story (and some AN bolts and a spare tailwheel yoke) are all that I have left today, so I’ll keep it.

I flew the Pitts into Oshkosh again (solo this time) on a year when they had the SR-71 Blackbird flying and on display (no supersonic flight, though). It was still fun but I missed having Jim to fly down with and park beside.

When it came time to leave Oshkosh that year, I had to start up and taxi from the show area to the flight line and shut down for a period of time waiting for something to clear. At that point the engine was warm enough to flood, and getting restarted was a fairly long and embarrassing debacle in front of a mass of spectators. It probably took fifteen minutes or more of hand-propping, with groans of disappointment at near-starts, and finally a round of applause (the most I would ever hear at any airshow) when it finally came to life. At that point I was pretty much exhausted and a little distracted.

When I took off from that show I was wearing only a headset so that I could hear the tower, intending to put the earplugs in after departure, but I lost track of them in the engine-starting fiasco. Somewhere halfway across Wisconsin I spotted the earplugs on the floor but couldn’t reach them. The noise was numbing my brain so I started to jostle around while flying inverted, hoping that they would fall to the canopy. It was sort of like a ball-in-maze game, and there were some vertical climbs and dives needed to get both of the foam plugs to negotiate the path around the seat bottom and straps to the top of the canopy where I could easily grab them.

That actually marked a turning point in my flying, because in the process of concentrating on chasing foam earplugs around the cockpit I realized that I had been flying more freely than ever before, without any of the usual apprehension of being in unusual orientations. I spent most of the trip back to Minneapolis fighting imaginary dogfights with features on the horizon or on the terrain below. A windshield bug was my gunsight, and I worked to keep my sight on target. It must have been a strange flight path, but this goofy experience maybe more than anything freed me from the structure and confines of the cockpit. It is difficult to describe, but it marked a change in how I viewed and tolerated acrobatics from then on.

The only wake-up incident that I ever had in the Pitts (other than close calls with other traffic and some early morning high-G greyouts) occurred two days prior to leaving for the EAA convention the following year. I was practicing some maneuvers about 30 miles north of my airport when I spotted low oil pressure – still yellow, but low yellow. I was above 3000 feet and at this point I was thinking save the engine, but I really didn’t know if this would get worse or not. I throttled back, but the pressure was fluctuating quite a bit and I still had some distance to go.

Maybe it was rational troubleshooting at the time or something else – I’m not sure how I tried this, but somehow I noticed that the oil pressure would go back to normal if the plane was flipped upside down. That could be managed, so the return trip was made hanging by the harnesses, occasionally flipping upright for few seconds to clear my head. It was a long straight-in approach with no pattern (airport traffic visibility was quite good upside down but hard to process). As soon as I was on a long final I rolled to upright and coasted in under yellow oil pressure. Aside from wondering what the heck had gone wrong, my biggest concern at the moment was that I feared someone might have seen the half-roll from the airport and would report it.

The incident was no big deal in the end, but the loss of oil pressure at higher RPM was a little difficult to troubleshoot back at the hangar. It was clear that the problem was somewhere in the inverted oil system, but after confirming that the ball valve was working correctly I had to look elsewhere.

I eventually had to stand between the wings and the spinning prop with the cowl open and the engine running well above idle (I did not like this at all), wiggling hoses until I found the culprit. It turned out that the hose running from the sump to the oil valve had partially failed. Upon inspection it was found that the inner neoprene wall of the stainless hose had ruptured and was occluding the oil path. I don’t remember if it was Aeroquip or Stratoflex that had an AD out for that type of hose, but I had presumably used the other brand that was not affected. It may have been a coincidence, or I may have accidently been given the wrong hose stock.

I raced to get a new hose made, and actually had it replaced and test flown in time to still make it to Oshkosh a day late, but weather came up. My window of opportunity closed and I never made it to Oshkosh that year, or ever again actually.

Subsequent years saw less flying in either the Pitts or the Aeronca. Other compelling interests, construction of a home even farther away from the airport, and finally a hand-propping induced hernia all led up to the sale of N68RH a few years ago. It appears to have changed hands again, but it is still flying – I recently found a YouTube cockpit video and many nice in-flight photos on the web posted by another owner.

Even over many years I never accumulated very many hours of Pitts time, partly because I rarely traveled cross-country in it, and an acrobatic flight for me was typically only about 45 minutes long. Add to that the short seasons, weather (it had to be nearly perfect outside to get me to make the trip to the airport), and increasing unwillingness to give up a whole evening or at least half of a weekend day for a short flight, and my foray into general aviation was over. There were other obsessions to pursue, one of which would be a different sort of flying – delving head-first into the hobby of flying radio control helicopters and airplanes.

Lasting Impressions

Not having a starter with the fuel injected engine was a mistake from the beginning. If the engine flooded on its own or because it didn’t start immediately when hand-propping you would be faced with a number of back-wrenching reverse flips to clear the fuel out. There were a few times that I was ready to just pack up and go home after finally getting the engine running. Even relying on a separate battery and jumpers would have been worthwhile, since most flights originated from my home airport and I rarely went to other airfields. I also could have installed a lightweight starter and battery and lived with the weight and balance limitations – I might still be flying today if it weren’t for the starting issues.

Takeoffs were always exciting and fun, as long as you could be confident that nobody was taxiing onto the runway ahead. My airfield no longer had an operational tower, even on weekends, and it was at times a very busy airport for general aviation traffic. It was fairly common for aircraft to taxi onto the runway without seeing aircraft on final approach. Another nasty behavior that seemed to develop over time was the habit that some pilots had of following the taxiway only half the length of the runway and then departing mid-field. You had to expect anything, which was even more of a concern in a Pitts with zero forward visibility.

This was mostly just irritating, but on one occasion I was already leveled for a numbers landing when I caught sight of a Cessna taxiing directly into my blind spot onto the runway in front of me, without any slowdown or hold. Fortunately the maneuverability and acceleration of the Pitts allowed be to quickly divert and recover to the right and parallel to the rolling Cessna. But for a moment my wheels were pretty close to his wing level, and he knew it.

This was not an uncommon event at this airport, regardless of what type of aircraft you were flying. As much as anything, flying the Pitts taught me how to be more wary and fly defensively.

Landings could be a challenge, but they too were always a rush. A power-off descent in the Pitts was dramatically steep, and too steep to play nicely with others planes on final approach. A flatter final approach that would keep the Pitts in line with the floater planes required a fair amount of power, which of course would leave the Pitts in a bad place if there was any power loss. On the other hand, a steeper power-off descent might have been safer in case of power loss, but it would have given even poorer visibility of the creeping Cessnas below. S-turns on final were a necessity at times to maintain some view of the landing area.

The narrow and short wheelbase of the Pitts contribute to its reputation as challenging plane to land. Lack of any forward visibility is another big factor. You have to look side to side to judge your runway centering.

Bill had taught me that the worst ground instability occurred in the transition between flying and taxiing. With runway contact and for the initial deceleration, the flying surfaces still maintain effectiveness. As the aircraft slows a bit, the surfaces become less effective, but the ground speed is still high enough that the spring-steered tailwheel is very ineffective. In this transitional time the control inputs need to be large and quick to make corrections. And of course as the aircraft slows, tailwheel authority increases as the plane transitions to a high and then low speed taxi.

The most unstable time on the ground roll out was in that transition between flying and driving, and judicious braking helped minimize the time lingering there.

Bill also taught me to loosen the shoulder straps on approach, get your head up, and be fast on the rudder and the brakes. Ironically, after coaching me on how to be fast on my feet we had a dual flight in the S-2, and he commented afterward about how I was micro-managing the rudder pedals, probably more than necessary. But I never changed my ways, and I think because of that initial coaching I never had any close calls or over-controlling issues on landing.

But once away from the airport and traffic, in that space of time between the rush of takeoff and the concentration of landing, the Pitts was the most perfect airplane I ever had flown or ever would fly.

Strapped tightly in the cockpit with a parachute and two layers of hearing protection, it was every bit the machine that I had daydreamed about for years after that 1970 airshow. Once acclimated to the drone of the engine you entered a world of altered gravity in your own personal, trackless, and virtually limitless roller coaster.

The constant-speed prop acted as hydrostatic transmission of sorts, shifting smoothly into low gear with the power to pull the aircraft vertically, and as you floated over the top of a loop and pointed straight down you could hear and feel it shift into high gear, accelerating toward the ground at an exhilarating rate. Once trimmed for aerobatic flight, the symmetry of the aircraft made flying in any orientation effortless compared to anything flown previously. Wherever you wanted to be, it would go.

I would try to do most of the standard upright maneuvers and some of the simpler low-G inverted stuff, but there were some areas I just could not go into by myself. Inverted flight was fine, but I was too chicken to do inverted spins or outside snap rolls. I never went past negative 4Gs, and that was from doing a relatively easy half-loop from inverted to upright. I tried several times to do the opposite, an outside half-loop from upright by pushing into a dive around to inverted, but every single time I bailed out (of the maneuver, not the plane) a little past vertical and rolled to safety. I probably would have felt better trying these things in an S-2 with a copilot, but that never happened.

Despite the cramped cockpit and its landing reputation, the Pitts was a comforting, if not comfortable airplane to fly, primarily because it would reliably respond to inputs and not wallow around like overloaded pickup truck. Even years later when flying radio control planes and helicopters I would find myself favoring more responsive and less stable aircraft. Having strong control response available and learning some restraint was always preferable to running out of control.

In my limited experience I found the Pitts to be a bluntly honest airplane, and I say that as a compliment. It is designed for performance and as such it leaves out some of the compromises that would give it a more docile behavior and tolerance for pilot ineptitude. In the S-1T there are no flat airfoils to favor upright flight, no twisted wings to soften stall characteristics. It’s as if to say – here are your surfaces, they are symmetric and pure, and they care not of earthly orientation. Understand their aerodynamics, manipulate them wisely, and they will behave predictably and give you joy. Use them foolishly and they could surprise you.

My daydreaming and night-dreaming flights as that naive teenager were somewhat different from what I would experience many years later. I had not anticipated the physical effects – I envisioned being at the controls of a plane but the world around me was a projection on a big omnitheater screen. There were no g-forces, no knee and groin bruises after flight. I had simply never thought it through that far – it was all fun and games without any of the pain, physical exertion, and occasional apprehension and disorientation. But despite these realities, the joy of unrestrained flight overshadowed everything else. Building and flying an airplane was a learning experience of a lifetime and one that I am thankful to have achieved.

More Pictures

![]()